Gustav Metzger, major artist

On Saturday I was at a conference in Cambridge organised to celebrate the exhibition of the life and work of Gustav Metzger at Kettle’s Yard. Do I hear the question “who?”, even from people who are well-informed about contemporary art. The problem is that he has, over the course of a heroically consistent career, created works based on processes rather than the depositing of artefacts as fixed and marketable commodities. If someone asks, “where do I go to see his works?”, the question is not easy to answer. For the most part his oeuvre is known through a very patchy visual record of photography and film, and recreations of the kind in the Kettle’s Yard show and earlier in the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford in 1998-9 (the publication for which I wrote an essay).

Arriving as a teenage refugee from Hitler’s Germany in 1939, he studied at the Cambridge School of Art. Some biographical details are at http://www.kettlesyard.co.uk/exhibitions/2014/metzger/ and in the excellent publication by Lizzy Fisher.

He was a pioneer of auto-destructive art and auto-creative art, in which processes driven by technologies and cutting-edge science create results that impermanent and unpredictable. Most famous are the remarkable liquid crystal displays in which wall-size panels undergo wondrous changes of form, colour and light. I devoted one of my columns in Nature to their Oxford manifestation (reprinted in Visualizations, OUP). I include the text at the end. At least the recreation in Cambridge is owned by the Tate.

Unlike many young radicals, Metzger has never compromised to become a maker of expensive collectables. His social and artistic mission remains, at the age of 90, undimmed by time and inevitable physical frailty. This mission is summarised in the “Harmony” declaration to which he contributed in 1970 (reproduced in the book of the show). Just two excerpts will demonstrate its prophetic nature:

The traditional Techniques of European civilisation for control of out environment have developed to the point of creating desperate problems that cannot be solved on their own terms…

The whole enterprise of science is a branch of the apparatus of production: of commodities, of war, and of consciousness. It has more or less autonomy depending on local circumstances. Up to now its relative independence has been both a precious freedom for the few, and a convenient myth for the many.”

I would now add to the second of these, which is very much of its time, “political imperatives based on the national economic demands and the trans-national dictats of big business”. Metzger loves true science, dedicated to the disclosure of the nature of things, as I try to argue in my Nature piece, below. He is to my mind one of the major artists of the second half of the 20th century.

Art that relies upon the witnessing of a process confounds our expectation that any act of making in the ‘Fine Arts’ should result in a collectable artefact – an expectation that we do not impose on theatre or musical performance. The work of Gustav Metzger is particularly infuriating in this respect. His programme of ‘auto-destructive art’, launched in his London manifesto of 1959, leaves behind no permanent object or enduring trace – frustrating mercenary dealers and acquisitive museum curators. His ‘aesthetic of revulsion’ which relishes forms and modes of expression that ‘are below the threshold of social acceptance’ insults the established criteria of those who aspire to appreciate ‘Art’. And his apparently anarchic media, such as the nylon canvases dissolved by acid spray into apparent nothingness, set him up as a prime candidate for ridicule by the popular press and those who decry ‘modern art’ as fraudulent.

The destructive processes which form one strand of his activity are a response to the events which marked his personal and political life. Born in 1926 as the son of Polish Jews in Nuremberg and exiled with his elder brother to England in 1939, Metzger’s student years were ravaged by a war in which his parents were immolated, and the art of retaliatory mass destruction was first practised at Hiroshima. In life as in art, he has fomented rebellion. In company with Bertrand Russell and fellow anti-nuclear protesters, he was one of those imprisoned in 1961.

Science – and this is where he qualifies for inclusion in our present context – has been a constant concern in his art. Science is neither automatically demonised nor gratuitously exploited. On one hand, he has savaged the way that scientific technologies have ruthlessly extended man’s destructive potential, forcing the old concept of ‘Nature’, ideally inclusive of man, to become the ‘Environment’, which is to be managed from ‘outside’ by mighty human agencies. And he bears witness, metaphorically in his auto-destructive acts, to the awesome ‘tearing apart’ and ‘annihilation’ practised by nuclear physics in its dismembering of the atom.

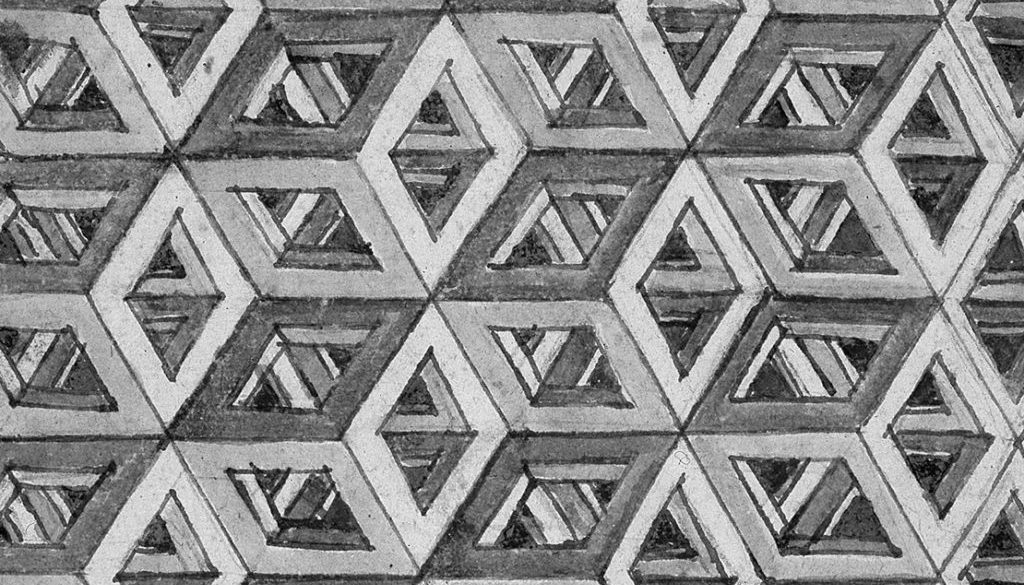

On the other hand, Metzger recognises that ‘each disintegration… leads to the creation of a new form’, a transformatory process that leads logically to the other side of his artistic and social coin – ‘auto-creative art’. Setting up physico-chemical reactions to produce growth and metamorphosis, ‘auto-creative’ works exploit the potential of such physical wonders as liquid crystals and new technologies, and most notably computing, to forge art-forms that serve as theatres of natural process. A central ideal is non-predictability, resulting in ‘a limitless change of images without image duplication’.

His most prominent creations in this ‘auto-creative’ mode are his liquid crystal projections, invented in 1965 and first manifested on a huge scale at concerts by ‘The Cream’, ‘The Who’ and ‘The Move’ at the Roundhouse in London at the end of the following year. For a series of exhibitions in 1999, the ponderous 1966 programme of twelve apparatuses operated by a dozen assistants, which operated less than smoothly, has been replaced by a computerised system. Six automated projectors, equipped with devices for the heating and cooling of slides of liquid crystals, work according to a non-repetitive programme to cast images through rotating polarised filers onto the walls of the gallery. The endless sequence of infinitely varied configurations and colours pulse with similitudes of organic processes, orchestrated according to individualistic timetables. They simultaneously suggest microbiological metabolisms, geo-physical phenomena, chemical reactions, physical processes and the artificial beauties of the kind of abstract art that rose to prominence in the 50s and 60s with the Abstract Expressionists. During a sustained viewing when they were on show in the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford, there were recurrent though non-identical resonances with the floating veils of colour on the canvases of Mark Rothko.

On one side of his coin Metzger displays our potential to become the agents of irreversible destruction; on the other he rejoices in our creative integration with the life-giving properties of nature. His mission fuses art and political meaning. He is intending that we should see that the choice of on which side coin falls is literally too vital be left to the short-term expediencies of commercial gain.